PASSCHENDAELE

(October and November, 1917)

"...I died in Hell

(they called it Passchendaele) my wound was slight

and I was hobbling back; and then a shell

burst slick upon the duckboards; so I fell

into the bottomless mud, and lost the light". . . Siegfried Sassoon

When one ponders the waste, stupidity, mud and gross loss of human life during the Great War, it is usually the battle of Passchendaele that comes to mind. This brainchild of Field Marshal Douglas Haig – also called The Third Battle of Ypres - officially began on July 31, 1917. Examining the general objectives, I guess it is possible to view the initial assault as worth attempting. It was hoped that smashing the German lines at Flanders would allow the allies to break through to the coastal ports of Belgium, causing considerable damage to the U-Boat offensive of Germany, as well as, causing serious damage to the German defensive strategy on their Belgian flank. The blundering and inexcusable waste of lives comes into play as it become obvious that Haig is willing to continue on with a poor plan regardless of weather conditions and German opposition. The full level of his poor leadership is seen when viewing the results: a gain of little importance with tremendous loss of life.

Four million shells were used to “soften-up” the German defences as the attack began with a resulting destruction of the water table and drainage system of this lowland region. Streams and creeks were obliterated. The attack commenced at the same time the seasonal rains hit the region. Men and tanks had huge difficulty moving on the field of battle. Artillery could not hold positions properly as the footings were placed on the soggy ground. German defences had taken on a strategy of housing the men in concrete “pill boxes” on the slightly

higher ground of the ridge giving their machine guns cover and an open field of fire to destroy the attacking forces. As the men strayed onto the battlefield, it was soon obvious that success would be almost impossible and slaughter guaranteed. Men who had the misfortune of falling from the duckboard walkways faced a death of drowning in the mud of the shell holes. As the summer worked itself into early fall, it was obvious that no great breakthrough was to happen and that the British forces would face a gradual reduction in their numbers, morale and chances for victory.

By October of 1917, the Canadian troops were called upon to enter the situation and bring about a successful conclusion to this disaster. It was hoped that not only would the battle be turned in favour of the allies but also, unofficially of course, save the career of Field Marshal Haig. By the time the Canadians arrived at Passchendaele practically no objectives had been met. General Currie, Commander of the Canadian Corps, wanted no part of this enterprise but was soundly over-ruled by the British High Command. In fact, they were prepared to send their most innovative and gifted officer packing if he showed any more resistance to the order. Currie did, however, manage to win the point that extensive preparations and planning would be needed and that time must be granted for the Canadians to prepare and hopefully avoid making the same errors that had caused so much suffering for the British and Australian forces.

The field as faced by the Canadians was full of mud, water, corpses, dead horses, barbed wire and miscellaneous wreckage of almost four months of battle. The trench lines were almost unrecognizable due to the water and mud. The Canadian plan began with the rebuilding of the transport systems and an attempt to drain the field as best as possible. German shelling, aircraft attacks and nature caused over 1500 Canadian casualties before the attack even started.

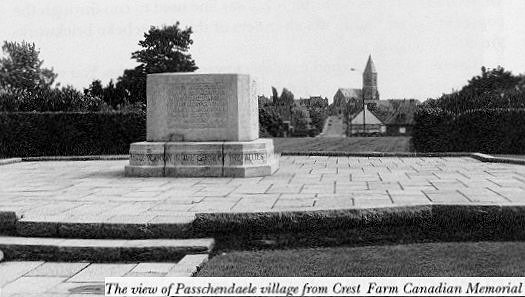

The Canadians attacked on October 26, 1917 behind a covering artillery assault. Movement would be in small steps rather than great frontal assaults on German lines. Gradual steps into German positions would be accomplished to cover each successive move of the troops. Fresh reserve troops would come into position within two days to spell those on the front lines. The first day saw almost 2500 casualties. The next bite into the German lines would be on October 30 following an even larger artillery assault. German concrete bunkers would be destroyed by the artillery – not through direct hits- which did little, but often by destroying the ground surrounding them and causing the footings to shift. Should this fail, the bravery of the men would prove to be a success. This strategy of taking steps to reach the objective was working but costly. By November 10 the ridge had fallen to the Canadians. The Germans were ordered to retake the position at all costs but could not.

By November 14, 1917 the Canadians, having done what was asked of them, retired back to the Vimy region. Their positions were taken up by British troops. Almost 15,654 Canadian casualties had been counted (Currie had warned the British High Command that victory would cause 16,000 casualties a month earlier). Nine Canadians had earned the Victoria Cross. Roughly two square miles had been taken at a cost of 500,000 casualties to the Allied forces. Field Marshall Haig was spared his career.

With little fanfare and a grudging recognition of their deeds, the Canadian Corps had proven to all that their bravery, planning, training and skill had made them the elite Corps of the allied forces. With this killing ground behind them, the Canadians would take up their positions by Arras / Vimy / Lens and prepare to take on the final German defences of the Siegfried Line and in fact, lead the final assault that would bring the war to a close.

last updated: July 6, 2006

Quick Links on TheGreatWar.ca Home Flanders & Vimy Ridge Major Canadian Engagements Beaumont-Hamel TheGreatWar Links Canadians Shot at Dawn WW II:Dieppe Tribute