Canada & the Battle of the Last 100 Days

As the war continued through 1917, the Canadians had moved their positions up from Vimy to take over the positions of the Australian and New Zealander's at Passchendaele. The battle for Passchendaele (a.k.a. the Third Battle of Ypres) had begun on July 31. Before the arrival of the Canadian forces 225,000 British and their allies had been killed or wounded. By November 12, 1917 Passchendaele was taken by the Canadians and after two days of unsuccessful German counter-attacks the Canadians were relieved by the British on November 14. The Canadians had suffered 15,654 killed and wounded.

The German spring offensive would retake this position from the British.

The German Offensive: Spring 1918

The end of 1917 also saw the Russian war effort disintegrate due to revolution. With Russia out of the war, German forces could be united in their attack on the Western Front. The American troops would not be a significant factor as they were not prepared to assume fighting duties. Although the U.S. had declared war in April of 1917, they were not prepared for war. By the spring of 1918 they were finally prepared to, primarily, relieve elements of the French army to the north east of Paris and allow the French to move toward the attacking Germans to the north-west.

The Germans had 178 divisions ready to attack by February of 1918. Their “new” tactics would involve using storm troops – a lesson learned from the Canadians at Vimy Ridge – attacking the weaker sections of the allied lines. The main body of troops would move in later. On March 21, 2,500 guns opened up on a 50 mile front of the British line. This successfully pushed the British back beyond the Somme River. Germans also attacked and successfully pushed back the French forces located to the south of Arras.

The Canadians expected to be next, as the British forces to their left and the French to their right had already been pushed back.

The following is taken from Arthur Currie’s speech to his troops in anticipation of this German offensive:

“Today the fate of the British Empire hangs in the balance. I place my trust in the Canadian Corps knowing that where Canadians are engaged, there can be no giving way. You will advance or fall where you stand facing the enemy. To those who will fall, I say, you will not die but step into immortality. Your mothers will not lament your fate but will be proud to have born such sons. Your names will be revered for ever and ever by your grateful country and God will take you unto Himself. I trust you to fight as you have ever fought – with all your strength, with all your determination, with all your tranquil courage. On many a hard fought field of battle you have overcome the enemy. With God’s help you shall achieve victory once more.”

It soon became apparent that no attack would come. The Germans had purposely avoided engaging the Canadian Corps. It was believed by the German High Command that any attack on the Canadian line could easily result in a dangerous “slowing down” of the offensive if not halting it altogether. The Canadians had never been defeated and seemed unlikely to be beaten back within any reasonable time-frame. Haig desired the Canadians to work as a part of the British line in a defensive manner but was swayed by Currie to have the Canadians go on the offensive.

It was realized that the Germans knew the Canadians to be the Allied storm troops – their leading of any offensive was expected. The Canadians employed trickery to convince Germans that they were now to be stationed back in Flanders and this led the Germans to believe Flanders to be the site of the next allied attack. The Canadians were actually moving in total secrecy - even from the rest of their allies - to Amiens.

Amiens

The code word used by the Canadians for security at this battle was "Llandovery Castle" a Canadian hospital ship

carrying both Canadian wounded and Canadian Nursing Sisters. The ship had been torpedoed and sunk in June of 1918.

Without using preliminary artillery but using tanks (effective early but out of commission later) the Canadians moved forward at 4:20 am on August 8, 1918. By 1:15 pm the Canadians had more than achieved their objectives. The German lines had been breached and the Canadians had pressed 13 kilometres into German held territory. The cost was high, with almost 4000 Canadians killed or wounded but the results were impressive; roughly 27,000 German casualties and approximately 5,000 taken prisoner. The "Flanders deception" had worked flawlessly. A German POW had expressed amazement that the Canadians had been his foe, as he was told by the high command that all the Canadians had been moved to Belgium. During the next 2 days, the Germans had been pushed back an additional 24 kilometres, 4 German divisions were "on the run" and 10,000 more prisoners taken by the Canadian forces. This victory had liberated 25 French towns and villages and put a stop to the German efforts to split the British and French armies. The German Spring Offensive had been stopped and the tide of the war reversed.

The result of this Canadian action is best verbalized by Germany’s Erich von Ludendorff, the general quartermaster of the German army, referred to this battle as the “black day of the German army”.

The Kaiser ordered an initiation of Peace negotiations

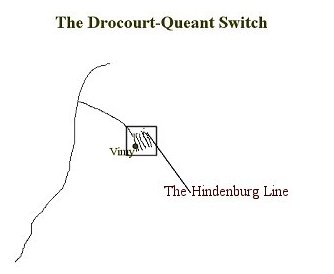

The Drocourt-Queant Switch

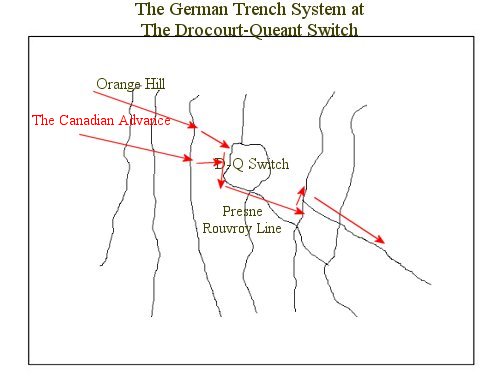

A week after the Amiens offensive was finished the Canadians were ordered back to the Vimy sector to to begin plans for the attack on the Drocourt-Queant line. Drocourt-Queant was the space or hinge of the main German defensive lines connecting the original defensive trench from 1914 to the new Hindenburg Line. The task was huge and the time for planning quite brief. Within 3 days the Canadians were to come up with a plan of attack through the old British and German positions plus the 5 new German defence lines. This would bring them to the Drocourt-Queant Switch which was 1.5 kilometres deep and supported by 3 lines of barbed wire positions.

The plan called for a" zig- zag" movement through the German positions. As the attack progressed and the German reinforcements came into play the Canadians would alter their direction to keep the Germans off balance and unsure of the Canadian objectives. By September 2, 1918 the positions had been taken and Germany's Drocourt-Queant line destroyed. Their position, now lost, caused the Germans to retreat behind the Canal du Nord and shorten their entire line along the front to compensate for the losses of men and the strategic effect of the loss of this hinge position.

After the taking of the Drocourt-Queant Switch,

Ludendorff admitted to the Kaiser, “We have lost the war: poor Fatherland”

Canal du Nord

The next objective for the Canadian Corps would be the Canal du Nord. This was a flooded canal, 30 metres in width

with a dry section to the south. Its level bottom and raised sides could prove to be disastrous for any army trying to take the position. Although not all the British General Staff would approve, the Canadian plan called for a daring movement across the dry section and then for the splitting of their forces; attacking behind the German positions to the left and taking Bourlon Wood to the right of the crossing.

On September 27 the engineers bridged the canal under fire and the Canadian forces were able to advance. By October 1, the Germans had thrown 6 divisions into the fight. They realized that the loss of this position would place the German forces onto open ground and little was left to stop the Canadian and Allied forces. On October 9 the Canadians attacked Cambrai and by October 11 had secured the entire district with their 37 kilometre advance into enemy territory. This action had resulted in the liberation of 54 towns and villages.

To Belgium and Mons

As the Canadians advanced, they crossed the Belgian-French frontier. Each day saw the German forces being pushed back further and further. On November 5, the Canadians would liberate Valenciennes. Although the Canadians met with success, the British forces were not as fortunate. It was decided that the British would boost their morale and attend the liberation ceremony at Valenciennes. The people of Valenciennes would not be allowed to honour those who had actually liberated their city - the Canadians were not included.

By November 9 the Canadians entered the outskirts of Mons. Mons had been the site of the first British "withdrawal" back in the fall of 1914. Rumours of an armistice began to circulate within the ranks. Hindsight after the war -- and a serious infusion of bitter and small minded slander on the part of Sam Hughes and his followers - have soiled the decision of Arthur Currie and the Canadian forces to take the city at such a late hour. It is easy to forget that the terms of the armistice were not known. Most - including the Germans - had believed that the land occupied at 11:00am of the 11th would remain occupied. Not being sure of the outcome, Currie had ordered the taking of Mons. Yes, in part to retake that which was lost by the British four years earlier, but also to insure the liberation of those Belgian civilians who had suffered so much for so long. One has to only view the footage of the people greeting their Canadian liberators to realize what this action meant to the people of Mons. General Currie would suffer the fate of so many other Canadians that deserved honours and recognition. His actions on the last 3 days of war would be used to batter him rather than honour him. The man who had saved so many lives with his planning and military talents would be attacked maliciously at home.

some wise words - ignored

Canada's General A. McNaughton's quote, referring to the armistice, speaks volumes:

"What bloody fools! We had them on the run. Now we shall have to do it all over again in 25 years."

"The peace, when it comes, must last for many many years. We do not want to have to do this thing all over again in another 15 or 20 years. If that is to be the case, German military power must be irretrievably crushed. This is the end we must attain if we have the will and guts to see it through."

- General Arthur Currie, Commander of the Canadian Corps

At 10:58 am on the morning of November 11, 1918, Private George Lawrence Price was killed by a sniper’s bullet. He would be the last Canadian killed on the battlefields of the Great War. Today, his grave is at St. Symphorien ( a few kilometres outside Mons) where he rests with the British casualties of the 1914 battle and the Germans who died during their occupation.

On November 11, 1918 at 11:00am The Great War stopped. An armistice would be in effect.

The "Peace Treaty" would take place in Paris the following year.

Quick Links on TheGreatWar.ca Home Flanders & Vimy Ridge Major Canadian Engagements Beaumont-Hamel TheGreatWar Links Canadians Shot at Dawn WW II:Dieppe Tribute