Theodora Goes Wild (1936)

| Production Company: | Columbia Pictures |

| Director: | Richard Boleslawski |

| Writers: | Mary McCarthy Original Story |

| Sidney Buchman Screenplay | |

| Cast: | Irene Dunne (Theodora Lynn) |

| Melvyn Douglas (Michael Grant) | |

| Thomas Mitchell (Jed Waterbury) | |

| Thurston Hall (Arthur Stevenson) | |

| Rosalind Keith (Adelaide Perry) | |

| Elisabeth Risdon (Aunt Mary Lynn) | |

| Margaret McWade (Aunt Elsie Lynn) | |

| Spring Byington (Rebecca Perry) |

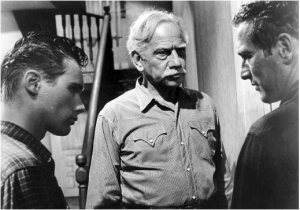

Never underestimate the skills required to bring off a successful comedy. Writing, directing, editing, scoring and acting must all be handled deftly and – above all – as invisibly as possible. It requires a light touch and impeccable timing. Not everyone can do it, and some actually fear it; many highly-respected, “serious” actors and directors want no part of comedy’s demands. In Theodora we find some of the most expert actors in Hollywood performing in a charming ensemble – sparkling Irene Dunne, droll Melvyn Douglas, irrepressible Thomas Mitchell and a wonderfully prim gallery of character actresses, including Spring Byington, Elisabeth Risdon and Margaret McWade.

It now seems absurd, but back in 1935 ace comedienne IRENE DUNNE was one of those actors who refused to do comedy. She was comfortable as a star of melodramatic “women’s pictures” (some called her “the Lady Gandhi of the ‘weepers’”) and meant to keep it that way. Ordered to star in Theodora Goes Wild, she fled to Europe for several months with her husband, certain the project would go ahead in her absence with someone else cast in the role. She returned to find herself still “stuck with the darned thing” – and the resulting film was a delight.

Happily for movie fans, after all that fuss and tension, Irene discovered she actually enjoyed making comedies, and made many more. Comedy gave her a much longer career than melodrama could have; the lurid glory days of women’s pictures were over when the Production Code clamped down in 1934. Theodora – the film she didn’t want to do – also brought Irene her second Best Actress Oscar nomination. Though she was nominated five times, she never won. She is widely considered “the best actress never to win an Oscar.”

Two of her co-stars here eventually won a slew of awards. To this day, only 9 performers have ever won the acting profession’s “Triple Crown” – winning film’s Oscar, Broadway’s Tony and TV’s Emmy awards. Theodora Goes Wild features the first two actors who ever did it, two of the most active and accomplished actors of the era. THOMAS MITCHELL was first in 1953, when he won the Broadway’s Tony for Hazel Flagg to complete his then-unprecedented trio (Mitchell’s 1939 Oscar was for Stagecoach and his 1953 Emmy for TV’s The Doctor). In 1967, MELVYN DOUGLAS became the second, with an Emmy for CBS Playhouse joining his Tony for 1960’s The Best Man and his 1963 Oscar for Hud. Douglas topped it off with another Oscar in 1979, for Being There. How Douglas got there is an unusual story:

MELVYN DOUGLAS was among the blacklisted actors in the 1950s and unable to find any work in Hollywood, a sorry state of affairs. But, thanks to the efforts of Actors Equity president Ralph Bellamy in New York, there was no political blacklist on Broadway. Douglas returned to his stage roots and rejuvenated his career. Much like Bellamy and Dick Powell before him, Douglas had been mired in lightweight movie roles for many years. His flair for light comedy typecast him, and as he grew older he tired of it. “The Hollywood roles I did were boring: I was soon fed up with them,” he recalled. “It's true they gave me a world-wide reputation I could trade on, but they also typed me as a one-dimensional non-serious actor.”

When he returned to movies in the early 1960s, it was with much meatier roles than he’d played before, in tough and cynical films such as Hud (1963), The Americanization of Emily (1964), I Never Sang For My Father (1970), The Candidate (1972) and Being There (1979).

The blacklist that destroyed so many creative people actually sparked Melvyn Douglas’ reinvention, and ultimately brought him a great deal more personal satisfaction with his work. He worked in projects he enjoyed until he died, at 80, in 1981. That’s quite the silver lining.

Melvyn Douglas’ granddaughter is current actress Illeana Douglas. She says she lives by this quote from him: “All acting, if it’s any good, is character acting.” She remembers family dinners that featured sparkling conversation and song. “He was very witty, very literate,” she recalls. “It was quite a legacy to grow up with.” He hoped she would be a writer, but a visit to a film set when she was a teenager helped steer her toward acting. Melvyn knew she was a big Peter Sellers fan, so he invited her to the set of Being There. She explains that Douglas and Sellers had actually known each other for years. “They met in the 1940s in Burma (during World War II) and met again in London during the '60s. Peter came up to my grandfather then and said, “Don't know if you remember me. I'm Private Sellers.” They often reminisced about the war days while on the set.” She feels deep ties to the movie, partly because both Melvyn Douglas and Peter Sellers died not long after it was made. “After he passed, my grandfather left me his Oscar for Being There. It's in my office next to a little picture of Peter and my grandfather, arm in arm, walking down the hallway with the moon behind them. I think my grandfather was 80 when he won that Oscar. So it's a reminder that there's hope for me yet!”

THOMAS MITCHELL was born in 1892 New Jersey to Irish immigrant parents. Tom followed his father and brother into newspaper reporting, and was good at it, but found he preferred writing fiction. Writing comic skits soon led to Tom becoming an actor. He gained valuable experience in his 20s, touring with Charles Coburn’s Shakespearean company, the Coburn Players. From 1916 to 1935, Mitchell was a major presence on Broadway, eventually involved in 29 productions – writing, directing, producing and/or acting. Tom made a silent screen debut in 1923, but didn’t return to films until 1936. At the time, he commented, “A lot of people say I've deserted my art because I left Broadway and the stage. Hell, I'm no artist. I'm a working man. I've got a trade just like any other mechanic, and I follow my trade where the work is. Just now it's in Hollywood, but I'm not tied to Hollywood.”

From the start, he was kept every bit as busy out in California as he had been on stage. By the time he made Theodora, his fourth film, versatile Tom was in such demand as a Hollywood character actor that he seldom found time to return to Broadway. Few actors appeared in so many renowned classic films: The Hurricane and Lost Horizon (1937), Only Angels Have Wings, Stagecoach, Hunchback of Notre Dame, Mr. Smith Goes to Washington and Gone With the Wind (those five all from 1939 – an amazingly prolific year) and It’s a Wonderful Life (1946).

In the 1950s, he worked almost constantly on TV, occasionally taking time out to appear in films such as High Noon (1952), and finally return to the stage (and his Tony award). Mitchell’s last film was Frank Capra’s Pocketful of Miracles (1961). He died the following year, at 70.

Stage actress SPRING BYINGTON made her feature film debut at 47 in a major role, playing devoted mother Marmee in Little Women (1933).

It wasn’t too much of a stretch; Spring actually was a widowed mother of two girls. That warm, gentle portrayal typecast her from the start. For the next 35 years, she played dozens of sweet mothers, dear maiden aunts and kind co-workers. Those “sweet” roles brought her work for the rest of her life, but being typecast meant she was often taken for granted.

Her best portrayals were the standout ones with some bite, and a bit of a twist: Mrs. Perry, Theodora’s relentless small-town busybody, eccentric playwright Penny Sycamore in You Can’t Take it With You (1938), avid gossip columnist Mary Sunshine in Roxie Hart (1942) and the off-kilter housekeeper in Dragonwyck (1946).

Spring became a mainstay of 1950s TV, starring in her own popular sitcom, December Bride, for five years as well as appearing on many other programs through the 1960s.

She really was a cheerful, optimistic woman. Asked once to explain her years of success, she smiled (sweetly, of course) and explained, “It's very simple. Lady Macbeth and I aren't friends.”

Notes by Paddy Benham