Stand-In (1937)

| Production Company: | Walter Wanger Productions – distributed by United Artists |

| Director: | Tay Garnett |

| Writers: | Clarence Budington Kelland (novel) |

| Towne, Graham Baker (screenplay) | |

| Cast: | Leslie Howard (Atterbury Dodd) |

| Joan Blondell (Lester “Sugar” Plum) | |

| Humphrey Bogart (Doug Quintain) | |

| Alan Mowbray (Koslofski) | |

| Marla Shelton (Thelma Cheri) | |

| C. Henry Gordon (Ivor Nassau) | |

| Jack Carson (Tom Potts) | |

| Tully Marshall (Fowler Pettypacker) | |

| J.C. Nugent (Junior Pettypacker) | |

| William V. Mong (Cyrus Pettypacker) |

Q: Hasn't anyone an answer for stupidity besides “that's the picture business”? A: I'm sorry Mr. Dodd, but that's the only answer.

Acting is an egocentric business. Loyalty and generosity among actors can be pretty rare, but there are some notable exceptions. Here is a nice one: HUMPHREY BOGART spent his first five years in Hollywood playing forgettable supporting roles. His big break came with the role of snarling criminal Duke Mantee in The Petrified Forest (1936). This placed him on a much more rewarding plateau, firmly among the studio’s gangster stars. Eventually, The Maltese Falcon (1941) and Casablanca (1942) bumped him up to a much higher level of stardom. He always maintained that he owed his success to LESLIE HOWARD. They had performed together in The Petrified Forest on Broadway to great acclaim. When Howard went to Hollywood to make the film version, he balked when Warner Brothers cast their go-to gangster Edward G. Robinson as Mantee. Howard said he would quit unless Bogart got to re-create his role, and he meant it. So Warners backed down, and Bogart got his big chance. (For his part, Robinson was happy to lose the role, always eager to escape the gangster stereotype he abhorred.)

Stand-In is the second and last film featuring Bogart and Howard. Please note that this satire was made by an independent producer, Walter Wanger. He had a lot more appetite for a Hollywood spoof than mainstream studios did. Stand-In features many familiar Warner Brothers actors, but it wasn’t their baby. General Services Studios – now called Hollywood General Studios – portrayed the Colossal Pictures lot. Howard and Bogart relished poking fun at the studio system, and along the way they take a bit of ribbing, themselves. Cerebral Howard was regarded as an “egghead” by the ever-lowbrow Hollywood community, and he certainly plays that part to the hilt here. Bogart brandishes a tennis racquet in one scene, a nod to his past: In the 1920s, during his tenure as a stage juvenile, Bogart introduced that immortal vacuous line “Tennis, anyone?” on Broadway. Stand-In was a happy shoot, made by people who enjoyed working together.

Today, Leslie Howard is best remembered for his absolute least favourite role, dreamy young idealist Ashley Wilkes in Gone With the Wind (1939). Howard did not want to make the Civil War epic at all. At 46, he felt he was far too old: “I hate the damn part. I'm not nearly beautiful or young enough for Ashley, and it makes me sick being ‘fixed up’ to look attractive,” he growled.

Producer David Selznick’s first choice for the role had been 25-year-old Tyrone Power, but 20th Century Fox boss Darryl Zanuck refused to loan him out. The film’s constantly-evolving screenplay and Selznick’s endless meddling did not inspire Howard’s confidence: “Terrible lot of nonsense – heaven help me if I read the book.” Even the costumes annoyed him: “I look like that sissy doorman at the Beverly Wilshire,” he scoffed, “a fine thing at my age.” Gone With the Wind was his last film in Hollywood. After playing Ashley, Howard returned to Britain to concentrate on making films for the war effort. He died at 50 in 1943, in a commercial plane shot down by the Germans, after going to Lisbon to deliver a lecture on the theatre. In 1952, Humphrey Bogart and Lauren Bacall named their second child, daughter Leslie Howard Bogart, in his memory. Leslie Howard Bogart has since grown up to become a nurse and yoga instructor.

Offscreen and on, Howard had a disarmingly vague, myopic quality, but friend David Niven said he was actually “not what he seemed. He had the kind of distraught air that would make people want to mother him,” said Niven. “Actually, he was about as naïve as General Motors. Busy little brain, always going.”

And Leslie Howard was certainly the polar opposite of romantically-clueless Atterbury Dodd. Years later, co-star Joan Blondell recalled, “He was adorable. Leslie Howard was a darling flirt. He'd be caressing your eyes and have his hand on someone else's leg at the same time. He was a little devil, and just wanted his hands on every woman around. He just loved ladies.” Accused of being a ladies’ man, Howard once protested that he “didn't chase women, but ... couldn't always be bothered to run away.”

Rose JOAN BLONDELL grew up touring the world with her family, performers on the international vaudeville circuit. She celebrated her first 12 birthdays in 12 different countries, many in the far East, before the family settled in Australia for a while. Back in the United States, Joan joined a touring company at 17, and was soon performing on Broadway. At 23, she appeared on Broadway with fellow newcomer James Cagney in a short-lived play, Penny Arcade, and they caught the eye of Al Jolson. He bought the screen rights to the play, then quickly re-sold them to Warner Brothers with the proviso that Cagney and Blondell be cast in their original roles. Why he added the proviso is anyone’s guess, for Jolson was not a benevolent man. He did Warner Brothers a very big favour in the long run, bringing the studio two of its biggest stars. Blondell went on to make six movies with James Cagney at Warner Brothers, more than any other actress. He found her a joy to work with. James Cagney said the only woman he ever loved, other than his wife, was Joan Blondell.

She was sassy, generous and good-natured – and that was no act. Joan was a loyal, treasured friend to her co-workers in the tough world of Warner Brothers. Bette Davis fondly called her “Rosebud”; Joan called her “Ruth Elizabeth” (Bette’s real name). Bette cherished their lifelong friendship as a rare touchstone to her past: “It was as if Ruth Elizabeth was still alive, whenever Rosebud and I were together.”

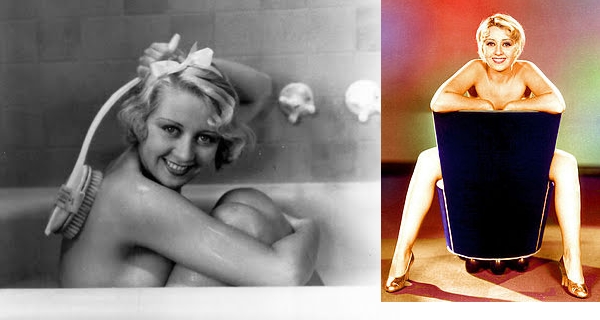

Joan resisted Jack Warner’s initial plan to change her name to “Inez Holmes,” but apart from that she was a very co-operative actress. Her charms were many: she had big blue eyes, a very warm smile and a remarkable figure, shown to great advantage in many racy pre-Production Code films. “I was a blonde with a very nice figure, and men thought I was cute,” she recalled. “They liked ‘cute’ – non-threatening, you know.” She was featured in most of the studio’s cheesecake roles – a blonde Betty Boop in the flesh, with a much sexier voice.

These films were most often shot by the studio’s ace cinematographer, George Barnes, who became her first husband in 1933. They had a son, Norman, before divorcing in 1936.

Then Joan married her frequent co-star, Dick Powell, and had a daughter, Ellen. When the marriage fell apart in 1944, Time magazine reported that according to testimony in the divorce court “when she objected to the incessant coming and going of guests, Powell crooned: ‘If you don't like it, you can get the hell out’.”

Three years later, Joan fell hard for dynamic impresario Mike Todd. Their marriage was a disaster on several fronts. Hard-living Todd blew through her life savings, gambling much of it away. After their divorce, Blondell did not marry again. True to form, she was generous in her assessment of her husbands: “Barnes provided my first real home, Powell was my security man, and Todd was my passion. But I loved them all.”

Blondell always downplayed her ambitions and abilities, but she was actually an expert, very talented actress. Her range was much wider than the cheerful gold-diggers and comic pals she is remembered for. She excelled in such dramatic roles as free-spirited Aunt Cissy in 1944’s A Tree Grows in Brooklyn – her favourite role – and earthy carny Zeena in 1947’s Nightmare Alley.

Expressive Joan thought little of minimalistic actors: “There's a fine line between under-acting and not acting at all. And not acting is what a lot of actors are guilty of. It amazes me how some of these little numbers with dreamy looks and a dead pan are getting away with it. I'd hate to see them onstage with a dog act!” Blondell was also a gifted writer. Her novel “Center Door Fancy” was published in 1972. She continued acting until the end of her life, despite a long struggle with leukemia. One of her last films was 1978’s hit Grease. Joan Blondell died on Christmas day, 1979, with her children and younger sister Gloria Blondell at her side. She was 73.

Notes by Paddy Benham