On the morning of April 9, 1917 the Canadian Corps attacked the German stronghold position at Vimy Ridge. The ridge, located about 10 kilometres to the north of Arras in Northern France and just south of the mines and factories of Lens and Lille, was a high ground that commanded the entire sector.

The Canadian Corps, comprising of the Canadian 1st, 2nd, 3rd and 4th Divisions united for the first time – over 100,000 men - was attempting to do what the British and French forces had tried from 1914 to 1916. Their attacks had gained little other than 130,000 casualties.

Failure in this action could result in the destruction of Canada’s army.

The Objective:

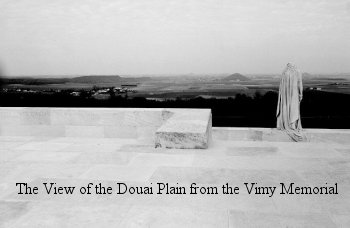

To fully appreciate the importance of Vimy Ridge, it is important to first realize a number of facts. The taking of Vimy Ridge was very important offensively as it was a key position of the German line in Northern France but it was even more important for the Germans to NOT lose Vimy Ridge. Their position in the entire region would be destabilized should the ridge fall into allied hands. The Ridge held a commanding view of the entire Douai Plain. Loss of the ridge would expose vast territory of German held positions to allied sight and allied guns. Vimy Ridge was the “hinge” of the German line as it protected the newly constructed Hindenburg line and also the length of the western front as it traveled north-west into Flanders and on to the channel. It is also important to note that upwards of 150,000 British and French casualties had been inflicted between 1914 and 1916 with no positive results.

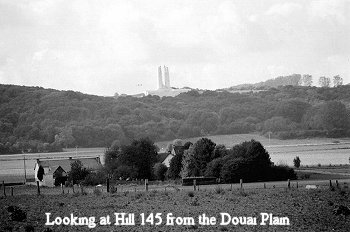

Vimy Ridge itself stands about 110 metres at the high point and runs for 8 – 10 kilometres in length. The allied side of the ridge was a long gradual slope which made its way to the crest where a sharp drop fell into the expansive Douai Plain. The reality of the geography gave the Germans a clear and uninterrupted sight line of all enemy advances while the Allies could only use aircraft to see beyond the crest and into enemy held territory. The Germans had developed a series of three highly fortified defensive lines utilizing machine gun, artillery and barbed-wire to produce ground that, in their view, could not be over-taken. To add to the defences above ground, the Germans had constructed a vast network of underground tunnels and living quarters safely placed below a danger zone from artillery shells – equipped with electricity, medical facilities and many of the “comforts of home”.

The attack on Vimy was a part of a larger British attack in the Arras region. The plan called for a massive movement across no-man’s land by British forces on either side of the ridge while the pressure of capturing the ridge fell to the Canadians. Should this high ground stay in enemy hands, it would insure failure on the battle front generally and cost countless lives in another failed push to break the German line.

Leadership:

Commanded by Lt.-General Sir Julian Byng and Major-General Arthur Currie, the Canadians were united into a single Corp and given what was considered by many, this impossible task. I personally think that one could never lavish too much praise on the vision and planning of these

two gentlemen. The war to that point had been one bloody massacre after another. Very little territory taken and no clear vision or plan developed to bring about a successful end to the

conflict. The Canadian Corp would institute a change in strategy and approach that would truly bring about the beginning of the end. The “let’s throw bodies in the path of machine gun bullets” approach to war was not going to cause the slaughter of the Canadian volunteers. Byng and Currie would re-vamp the old habits and inflict the first allied victory of the war against the German lines. An offensive strategy had been developed – a Canadian offensive strategy!

Currie and Byng had been a team since the horrific battles around Ypres at Hill 62, Sanctuary Wood and Mount Sorrel of 1916. Currie had been a leader in the Canadian forces at St. Julien during the gas attacks in April 1915. As a Canadian observer, Currie had witnessed, first hand, the problems faced by the French at Verdun. Unlike many of their counter-parts in the High-Command, these men learned from past mistakes.

They were not going to lead the Canadian Corps into battle, armed with the failing plans of the Somme or Verdun.

Innovations

The Platoon System:

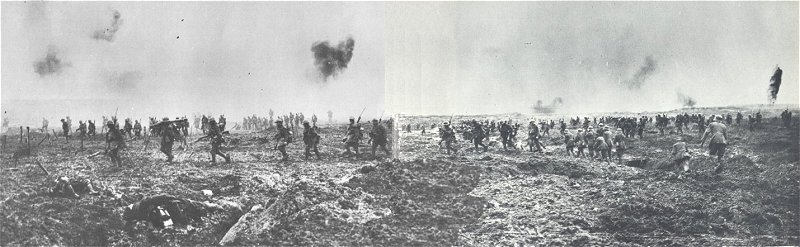

Up to Vimy, attacking forces threw wave after wave of infantry into the battle. These close-packed soldiers had little chance to succeed against the artillery, machine gun fire and barbed wire. The results were usually large casualties and little

success. The Canadians developed a system of placing specialists in machine-guns, bombs (grenades) and rifle specialists within a single platoon. These platoons would strike at the enemy, not in a straight line, but in a much looser action where German defenders had less chance of merely mowing down the attackers. This attack would find the attackers able to cover their own advances.

Communications:

Officers would stay more closely with their platoons, able to adapt and direct actions much more effectively and quickly. The men would also be fully briefed as to their objectives. Maps and rehearsals would be provided to each man. This would end confusion in the attack and bring the men more fully into the over-all objective of the attack. Should officers be killed, the attack could continue as planned. By the time the attack had begun, 21 miles of signal cable and 66 miles of telephone wire had been buried on the battlefront. The corps had dug 11 underground tunnel-ways to aid in the movement and protection of the troops. These underground roads were equipped with electricity, medical stations, supplies and rest stations. Portable bridges were built to assist in the movement of artillery pieces over the more difficult terrain and trenches.

Indirect Machine-Gun Fire:

Up to Vimy, machine-guns were primarily a defensive weapon. Their obvious advantage again the infantry kept them in place at the trenches and successfully wiped out many a brave man. With over 400 bullets firing per minute, per gun, bravery meant little. The Canadian Corps decided to put these defensive traits into action while on the offensive. Thanks to Lt.-Col R. Brtinel’s plan of “indirect firing” onto exact enemy positions both day and night, movement ceased at the German lines. Raids proved too dangerous and repair of barbed-wire almost impossible. The machine-gun fire became a supplement to the artillery barrage. During the attack, the lighter weight Vickers guns would be set up along with the Canadian advances providing both cover and a true offensive power designed to keep the German troops from attempting their usual defence.

Artillery Preparations:

The Canadians set up a massive strike capability with their field artillery. Almost 250 heavy guns and about 600 lighter gauged field guns were aimed at enemy positions. For three weeks, Canadian guns, hammered at German positions. Previously mapped German machine-gun and artillery positions were targeted as the attack began – silencing the guns and not allowing the Germans to move their emplacements. An average of 2,500 tons of shells rained down on the German positions daily. Far back in the German lines, transportation and communications positions were destroyed, stopping food, ammunition and fresh troops from reaching the front lines. Feeding the Canadian guns was a network of rail lines built to bring the huge numbers of shells into position. Special fuses were developed for shells that would cause an almost instantaneous explosion, designed to take out enemy barbed wire. One of the more tragic features of the British barrage at the Somme had been their inability to take out the barbed wire. During the week preceding the attack (the “week of suffering” as the Germans called it) over one million shells were fired at Vimy Ridge.

The Rolling Barrage:

A plan had been developed to attack the German lines using both the infantry and artillery in concert with each other. After almost 3 years of war, the German defenders had been accustomed to waiting for the end of the artillery to move from their protected positions and man their machine-guns with ample time to kill the attackers. The Canadian plan called for artillery to keep an exact pace in front of the Canadian troops moving across “no-man’s-land”. A well-rehearsed movement of man and shell, moving at a pace of about 100 yards every 3 minutes would attack the enemy trenches. This would provide a dangerous but effective cover for the Canadians. German machine-guns were kept silent as gunners stayed protected within the tunnels and trenches. It also, afforded an element of surprise as many Germans left their positions to face their attackers only to find the Canadians already at their trench.

Good Intelligence:

Nothing was left to chance. As mentioned above, enemy positions were mapped in preparation for the final artillery assault. Microphones placed through-out “no-man’s-land” were triangulated enemy fire. Aircraft and balloons spotted where possible and maps and information gathered from trench raids all put together a picture of the German defences. German artillery battery positions were calculated and machine-gun nests plotted – most to be devastated on the morning of April 9. In charge of this task was Lt.-Col. Andrew McNaughton, hailed by many as the most talented artillery man on the front. By the attack, McNaughton and those manning the Canadian guns had destroyed about 85% of the German batteries. Preceding the attack, trench raids were carried out to glean as much information of the enemy terrain as possible.

April 9, 1917:

On April 9, 1917 – Easter Monday – at 5:28 am the battle was engaged. The weather was a combination of snow and sleet. Underground mines were exploded, gas shells fell onto German positions and transportation routes, artillery began to hit

German positions and machine-gun fire swept the enemy’s positions. Over 11,000 guns (including British pieces) opened up on the ridge. The Canadians kept to their timetable and followed their detailed plans. By early afternoon, 3/5 of their objectives were taken. Thousands of Germans were taken prisoner and many thousands more had been killed. Still to be taken were the high ground positions called “the Pimple” (largely the responsibility of the British forces attached to the Canadians and Hill 145 (the highest ground – site of the memorial today). By the morning of April 10, Hill 145 had been taken – largely due to the incredible efforts of the work battalion from Nova Scotia. By April 12, the Canadians had reinforced those attacking “the Pimple” and after great effort had taken this from German hands as well.

By the end of the battle, all objectives had been met. Canadians had established themselves as an elite fighting force. The German line had been soundly breached and the Canadians had fended off any thoughts of a German counter-attack.

Unfortunately, this victory was not to be the sweep through the German lines that it could have been. Allied high command had not prepared for such a breakthrough. There were no British battalions ready to carry on through the breach in the German lines. Both the French and British offensives of that month failed.

It has often been said that Canada’s sons left their home as young colonials but returned as Canadians. Vimy is indeed the birthplace of “Canadian Nationhood”. The price was heavy: 10,500 casualties, including 3,598 dead.

May They Rest in Peace - Never To Be Forgotten

Vimy Ridge As Seen From The Douai Plain

Inside Vimy's Tunnels

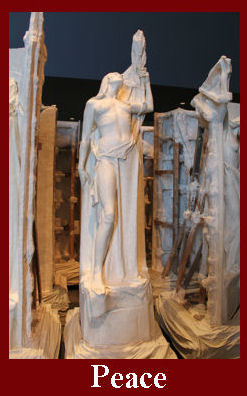

A Section of The Statuary of The Vimy Memorial

The Original Walter Allward Plaster Sculptures

As Displayed at The Canadian War Museum in Ottawa

last updated: December 2022

-------------------------------------------------------

This animation, provided by Paul Amirault, recreates pivotal elements critical to the successful engagement at Vimy Ridge April 9, 1917. Key to the movie, was the accurate re-creation of the battle area of Vimy Ridge. To this end, one highly detailed colour battle map that accurately depicted both the British/Canadian trenches, the German trenches and the topology was key in the reconstruction

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KWGBDg3rbe8

additional information and Photographs can be found on TheGreatWar.ca's

Photo Gallery and

Touring Vimy and

Flanders sections.

....

back to Canada & the Great War