This page was originally launched when I (Adam Sol) was a Ph.D. student in English at the University of Cincinnati. Guidance was being provided by Professor Robert Arner. At the time it seemed a pretty strange thing to put information about an early American press builder on the Web, when it's the Internet that appeared to be on the verge of overthrowing the printed word once and for all. However the responses I received were very enthusiastic and ranged from replica-builders in Seattle to historians in Washington, DC., and I was encouraged to continue work on the site, despite the fact that my research (and career) has taken me elsewhere.

If you're interested in a more thought-out disclaimer, here it is. Since there has been a fair amount written in various works on Ramage, most of what this page is is a compiling of materials from various sources. I hope that this will help scholars of the field, as well as potentially ignite interest in those who are newer to the material than I am.

Now that the page is up and running again, I plan to move things around a bit to make things easier to navigate and read. Suggestions and comments are always appreciated.

According to Robert Arner, he filed for citizenship on February 13, 1798, sponsored by John Innes, who was a printers' joiner -- that being, a "builder and repairer of wooden presses"[Saxe 69].

By 1799 Ramage was advertising himself as a printers' joiner. Apparently (again this from Arner) he and Mark Fulton, another Scottish joiner, bought out Mr. Innes, and took up business at 77 Dock Street. The partnership ended in May of 1800, from which time Ramage worked on his own.

Moran reports that by 1800 Ramage was manufacturing his own common presses, and by 1807 making his own modifications [47]. Ramage's improvements on the wooden press eventually made it the most popular press in the early years of the 19th century.

A discussion of these technical innovations is below.

Elizabeth Harris notes that the papers of Matthew Carey are the most well-known primary source for information on Ramage. According to these papers, in 1805, Ramage sold a press to Carey for $130, which would be "his basic price for a number of years to come" (Harris 14). This is notable considering the fact that other press builders of this time might charge as much as $400 dollars.

As Saxe writes, Ramage "became widely known as the maker of inexpensive, durable, well-made wooden presses that were ideally suited for smaller country newspaper offices." [69] He adds that "by the year 1837 Ramage was reported to have manufactured over 1250 presses of all kinds."[71]

Marc Eric Sanders similarly asserts that "Ramage dominated the wooden printing press manufacturing industry for nearly half a century. . . His work represented the height of the industry." [90]

With the emergence of the iron hand presses in the 1820s, Ramage began to incorporate iron into his designs, at first making a press which was "part iron and part wood," and which "dispensed with the cap and head, combining them into one cross-piece, and the hose by using springs on two sides to lift the platen" [Moran 47]. By 1820 Ramage would be making presses completely of iron, most notably the Ruthven in 1817, the Philadelphia in 1833, which "had a distinctive wrought-iron frame with a triangular top," and the American in 1845, which was invented by Sheldon Graves. [Moran 83] These presses would never fully compete with the emerging Stanhope and Columbian Presses, but Ramage would continue manufacturing them until his death in 1850, at the age of 78.

Even after the emergence of the iron presses, the Ramage press was favored by American pioneers for its portability, and his presses eventually worked their way across the United States. Moran states that "the first printing press in New Mexico" was a Ramage, which was "brought over the Santa Fe trail by wagon. . . in 1834." He also claims that the first presses "in Utah (1849), the State of Washington (1852) and possibly Colorado (1859) were Ramages."[47]

Ramage was a respected member of the Philadelphia community, and was a member of the St. Andrews Society, which was "a group of Scottish immigrants from all socio-economic levels" [Sanders 90]. He also sat on the Board of Managers of the Franklin Institute (eventually even becoming a Life Member) and was an honorary member of the Philadelphia Typographical Society. [Sanders 90-91]

Sanders again:

A few days after his death on July 9, 1850, the Society drafted a resolution which referred to 'the loss deeply to be deplored both by the society of which he was a bright ornament and most faithful officer, and by the Scottish emigrants of whom he was the true friend and able assistant.' The resolution further stated, 'As a husband and father he adored and delighted his domestic circle; as a friend he was earnest and disinterested; as a citizen public spirited and liberal, and as an artist ingenious and successful.'" [Sanders 90, who apparently got this quotation from the Hamilton text, p 6-7]Ramage was succeeded by Frederick Bronstrup (1811-1900), who continued to build and adjust the Philadelphia renaming it the Bronstrup, from 1850 to 1875.

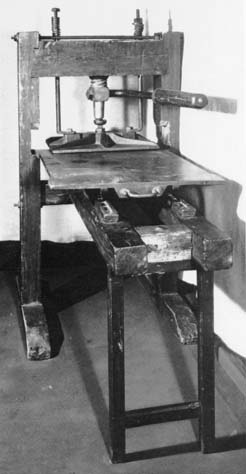

The central part of the impression assembly was the screw, which, when the assembly was "pulled" by a rod, pushed down a wooden platen, which pressed the inked type onto the paper. According to Isaiah Thomas, the screw of the common book press was

uniformly two and a quarter inches in diameter, with a descent of two and a half inches in a revolution. . .Ramage enlarged the diameter of the screw to three inches, and where much power was required to three and a half inches, and at the same time reduced the fall in a revolution to two inches, which very nearly doubled the impressing power, but decreased the rapidity of the action. It was an improvement made necessary by the finer hair lines the type founders introduced, requiring increased power in the press, and the reduction in the descent of the screw to one-half an inch was met by a more careful finish of the frisket and its hinges, which were made to slide freely under the platen in a space of half an inch. [40]According to Moran, Ramage also had the platen "faced with brass, and it was fastened with four bolts instead of cord lashings."[47]

Thomas reports that Ramage presses were made of "Honduras mahogany, with ample substance and a good finish, which gave them a better appearance than foreign made presses, and they were less liable to warp." [40-41]

However, in order to "facilitate production," Ramage "stripped his designs of almost all decorative flair." [Sanders 152] This also helped him keep prices down, and added to their portability.

John Ruthven, a printer from Edinburgh, patented a press made wholly of iron as early as 1813 [Saxe 71]. By 1817, probably through his connections with his homeland, Ramage was making the Ruthven press, though as Arner states, it is not known whether he was "simply serving as Ruthven's agent" or if another kind of arrangement had been made. There is some disagreement from here on how committed Ramage was to making the Ruthven press. Harris and Moran have written that Ramage soon left off the Ruthven Press in favor of more popular types, but Arner has turned up evidence that shows evidence of Ramage sticking to it rather tightly, at least until he began making the Philadelphia in the 1830s. My guess is that Prof. Arner turned up evidence that Harris and Moran didn't know about at the time. Hopefully he will provide me with some of that material to support his claims here.

Either way, Ramage still tinkered with the design. Sanders again:

Ramage, keenly aware of his European competition, took steps that would ensure his continued success. The Stanhope sold well in England from its inception and Ramage knew he had to satisfy the demands of American printers or they would turn to England and begin importing one-pull presses. He reacted with a daring redesign of the common press.It's rather unlikely that Ramage himself invented all of these modifications, but he was clearly the one who made these changes accessible and successful in the marketplace. He continued to modify the designs of printing presses as long as he continued making them.By about 1820, he had produced a smaller printing press which incorporated a number of new principles. He shortened the cheeks and dispensed with the cap of the press. To hold the cheeks together at the top he utilized two iron bolts which extended cheek to cheek, directly over the head. He discarded the hose, supporting the platen instead with iron rods which projected through the head. Iron coil springs retained these vertical platen support rods automatically raising the platen after each impression. This saved the printer time and energy. He manufactured the platen of cast iron, offering a truer and more durable surface. He also replaced the wooden plank and coffin assemblies with a cast iron bed and frame which slid in and out on cast iron rails. The only ornament Ramage left on the wooden members of the press was a simple radius on top of the cheeks and ends of the feet. He even managed to eliminate half of the till. He took advantage of every available opportunity to simplify the design.[159]

Email Adam Sol about the page.

Back to top of the page.

Go to Tarshish, Adam's homepage.