Kanu Links

The Nastawgan

Traditional Routes of Travel in the Temagami District

by Craig Macdonald

I included this following article because it applies equally to

the Spanish River area. The article is copyrighted © and was published in the book "Nastawgan

- The Canadian North by Canoe & Snowshoe", 1985 Betelgeuse Books, Toronto.

The Author of this article, Craig Macdonald, and the publisher, Betelgeuse Books, have

kindly given permission to post this webpage.

E.K., August 1999

Nastawgan is a word still in common usage amongst the older, native-speaking

Indians of Northeastern Ontario. Nastawgan are the ways or the routes for travel

through the land of the Temagami district in Northeastern Ontario, just south of the

height-of-land.

Before the advent of roads and railways, waterways provided the principal

routes for travel and communication over much of the shield country of North-eastern

Ontario, including the Temagami and Lady Evelyn watersheds. It was much easier to travel

on the waterways than to traverse the rugged, rocky and densely forested terrain.

Waterways were used not only in the summer for canoe travel but also in the winter for

travel by snowshoe and toboggan. In many instances, the winter routes of travel varied

little from those used in the summer.

A trail network based on waterways provided a wealth of natural

campsite locations as well as access to fisheries which furnished a major portion of the

summer diet for early residents. Unlike land based trails, full exposure to biting insects

was limited to campsites and portages. Onigum or canoe portage trails were

maintained to by-pass unnavigable portions of the route: rapids, falls, heights-of-land

between waterways and floatwood jams known to fur trade canoemen as

"embarrasses".

Bon-ka-nah or special winter trails over land were equally

important. In winter, the chief obstacles to snowshoe travel were and still are open

water and unsafe ice, found where moving water resists the formation of ice. Sometimes the

Algonquin Indians simply extended the trail at the ends of portages in order to reach

calmer water with sufficiently thick ice for safe travel. Rivers with strong current

extending continuously over long distances posed a greater challenge, especially where

there was no space for travel along the shorelines. In such cases they made longer bon-ka-nah.

Bon-ka-nah were also constructed specifically as shortcuts to reduce the length

of winter travel routes.

Although onigum (portages) and bon-ka-nah (winter

trails) were part of the nastawgan, there were advantages to using waterways for both

winter and summer travel in preference to the land trails. Probably the most important

advantage was the ease of transport for equipment and supplies. Before the arrival of

Europeans, the native population did not have horses or cattle to serve as beasts of

burden. Without the use of the wheel, summer land transport was limited to dog travois,

dog packs and to what a person could drag or carry On lengthy land routes this imposed

severe weight restrictions.

Canoes, on the other hand, permitted extraordinary loads of equipment

and supplies to be transported even on the most difficult routes. For every mile of travel

only a fraction was covered by portage. Because of the relatively small portion of the

total distance requiring portaging, several trips could be made over each portage without

significantly slowing progress. As long as the cargo could be subdivided into units which

could be carried, large loads were transported with relative ease. Another advantage was

the limited maintenance required to keep the routes passable. On the water portions,

maintenance was restricted to cutting out fallen trees which obstructed travel on narrow

creeks. The portages or onigum themselves received maintenance similar to that of any land

trail, but being short they were relatively easy. Most work consisted of breaking down

obstructing branches and sometimes marking the route by blazing trees with an axe. Fallen

trees blocking portages were rarely removed, especially if cutting was involved. Either a

few branches were knocked off so one should step over the tree, or the trail was simply

re-routed around the obstacles.

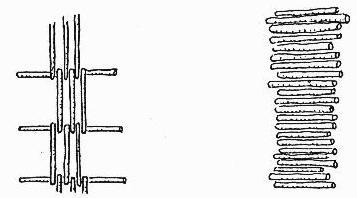

Onigum passing over wet areas received greater attention. Logs

were layed on the ground to improve footing. In some instances, metigo-mikana was

used to replace simple logs for traversing wet areas. Unlike the corduroy of the pioneers,

metigo-mikana was laid longitudinally in the direction of travel so that a minimum of

cutting was required for construction. The walkway was often 3 poles wide, connected by

cross stringers which provided lateral stability. Cedar was the preferred building

material. Joints were often notched and secured by spruce root.

On the left is metigo-mikana (separation in walkway members

exaggerated to show construction details), on the right is typical pioneer corduroy for

wheeled traffic.

In the winter, use of frozen waterways

meant limited trail maintenance and relative ease of transport. Travel on frozen lakes

proved much easier than on trails over rugged terrain. Not only did the lakes

provide a level surface for pulling toboggans and sleighs, but the wind-packed snow

frequently encountered on lakes was more easily traveled than the deep, soft, mid-winter

snows common to sheltered land trails. A man in good physical condition could pull over

frozen lakes a load of 90lb. on a toboggan all day without tiring. On the uneven terrain

of many land-based trails, this would prove an exhausting if not impossible task. Onigum

constituted such a small portion of the total distance that the deep unpacked snow of

these portage trails could be profitably broken by snowshoe in advance of bringing across

the load without too much loss of time. If the load still proved unmanageable, it was

broken up and dragged across in portions.

Depending on weather conditions, as much as three months of the year

was poor for travel along water routes. Freeze-up and break-up have always been a most

difficult time for wilderness travel in the Canadian North. For a period during freeze-up,

the open season for canoe navigation could be extended by making arduous land detours

around shallow lakes which had already frozen.

Otherwise, the traveler could use a canoe-sleigh to transport the canoe across the ice. If

the ice was not too thick, it could be broken with a paddle or axe to reach open water. Barres

d'abordage or canoe shoes could also be added to the outside of the canoe's hull to

protect it from ice damage, but soon even this became impossible. Travel on the water

routes was usually suspended until the ice thickened sufficiently to support at least the

weight of a man.

Even now most experienced wilderness travelers consider spring breakup

to be the most unsafe time to travel, because of the

unpredictable strength of the ice. Sometimes, however, the period between travel on ice

and travel on open water can be as little as two days. Traditionally, travel on weakening

ice-plates was accomplished by the ingenious employment of the canoe-sleigh. A canoe was

secured in an upright position on top of the sleigh and the travelers walked along the

surface of the ice holding on to the ends of the canoe. Often two or three dogs were

harnessed to assist with the pulling of the load. If the ice gave way, the travelers

quickly jumped into the ends of the canoe, preferably before getting wet and thus very

cold. The sleigh would then be untied from the bottom of the canoe and placed inside. The

cycle would be completed by running the canoe up on solid ice and reloading. As this type

of travel was slow and dangerous, it was usually undertaken only in times of extreme

necessity.

Utilizing a water system for winter transport required

good knowledge of travelling on ice. Likes with large water inflows in proportion to their

total surface area were the most hazardous. These lakes are prone to water level

fluctuations which stress and weaken the ice plate along the shoreline and encourage the

development of surface slush and air holes. Furthermore, the ice

surrounding inflows can be dangerously thin, not unlike ice in other areas with current,

such as narrows or obstructing shoals. Underwater springs whose water is several degrees

above freezing create an additional hazard. As a result, well defined routes of travel

were sometimes established on the most dangerous lakes.

If the route was to be followed frequently, the designated snowshoe

path was often marked at regular intervals with evergreen boughs, This was done in

anticipation of the packed trail becoming obscured by drifting or new fallen snow. Even if

covered with new snow, a packed trail provided a firmer base for sledding and snowshoeing.

Since the packed trail was elevated above the

surface of the ice there was less chance of encountering slush that would freeze onto the

snowshoes and the running surfaces of the sleighs.

Slush was a problem. Slush is often created by heavy snowfalls

depressing the surface of the ice so that water seeps up through cracks in the ice to

flood the lower layers of snow. When insulated from the cold by additional layers of snow

above, the slush sometimes persists for weeks before it eventually freezes. By packing

down a trail on snowshoes, the upper layers of compressed

snow lose their insulating value, thus permitting the underlying slush to freeze, During

windy weather, the trail was often packed down to a double width so that the track did not

fill with drifting snow before the slush had a chance to freeze. If such an effort

was made to secure passage, the trail was often marked with boughs for possible reuse

later that winter. Such track preparation and marking naturally reduced the daily distance

which could be traveled hauling sleighs, unless people were sent ahead of the main party

to do this work. Usually an hour lead time was needed to freeze the surface of the slush

sufficiently for passage with

sleighs and toboggans.

For the bon-ka-nah or land trail portions, extensive use

encouraged an increase in the amount of trail maintenance undertaken. This included trail

marking by blazing trees, and greater efforts to remove wind falls and overhanging limbs.

Since side sloping trails were very difficult to negotiate with

toboggans and sleighs, the surface of the trail was often leveled with a snow shovel at

the worst locations. Leveling was especially needed where the trail traversed the sides of

hills. Shovels were also used to fill in the hollows along the trail if heavy freighting

was to be undertaken.

Seepage of ground water was another problem. Since water coming from

below the ground is several degrees above 0șC, it resists freezing even in very cold air

temperatures. Rivulets of ground water cannot easily be detected when they flow under the

surface of the snow. However, when a winter trail was packed down, the flow of water often

melted away the entire layer of snow within a few hours. To repair the trail at these

locations, it was common to cut evergreen boughs and place them over a series of sticks

laid in the washout, thus creating an insulating mattress of vegetation. Snow was then

shoveled over the boughs and packed down with snowshoes to freeze and create a snow

bridge. The warm water could then pass under the trail through the sticks and boughs

without melting away the surface of the trail or the snow bridge.

Occasionally, it was necessary to construct simple bridges or ramps.

The bridges were used for spanning open creeks or sharp gullies while the ramps were made

to facilitate scaling of abrupt rock ledges along the trail that could not be bypassed.

Most ramps would take the form of a ladder with two outer, spanning poles connected by a

series of cross rungs. The larger structures were rarely "brushed" with boughs.

Instead the sleighs and toboggans were hauled up over the bare wood rungs. This permitted

snow to pass through the structure, thus preventing a buildup which would allow the

sleighs and toboggans to slip off the side of the span. These trail improvements were

always undertaken only to the extent warranted by normal use. Travelers put in the minimum

of work needed to keep the routes passable throughout the winter.

Some exceptions to this generalization did develop in the

Temagami district. After contact with Europeans some routes were significantly upgraded

winter freighting by employees of the Hudson's Bay Company.

Up until the 1940s, over 75 well maintained

bon-ka-nah existed in the Temagami area. Macominising (Bear Island), Wa-wee-ay-gaming

(Round Lake), Shkim-ska-jeeshing (Florence Lake), Abondiackong (Roasting Stick),

Non-wakaming (Diamond Lake) were major intersections in this system of winter trails.

Depending on the nature of the local topography and waterways, the bon-ka-nah ranged from

a few hundred meters to many kilometers in length. Often the shorter bon-ka-nah formed

links between a chain of ponds used only for winter travel. For example, the winter route

from Maymeen-koba (Willow-Island Lake) to Ka-bah-zip-kitay-begaw (Katherine Lake) followed

a series of small ponds and connecting bon-ka-nah lying between the two branches of the

Manja-may-gos (Lady Evelyn River).

It took detailed knowledge of the terrain to

determine the best location for many of the longer bon-ka-nah. Much evidence survives of

the skillful use of swamps and geological faults in order to keep the trails direct and to

minimize climbing. An outstanding example of using geological faults for easy passage

through hilly terrain can be found today in a long fault which runs from Scarecrow Lake

adjacent to lshputina Ridge, the highest elevation in Ontario, cross country through

Florence, Diamond, Jackpine, Net Lakes and the Ottertail River to Lake Temiskamimg. No

less than 14 bon-ka-nah are located along this great fault.

The onigum and bon-ka-nah of the Temagami

district total over 1,300 in number. But inter-related network of summer and winter trails

represents only a small portion of a larger system of nastawgan that until a few

generations ago covered most of the Precambrian Shield country of eastern Canada. They

defined the way of the wilderness traveler. Fortunately, the nastawgan of the Temagami

district have remained in a largely unaltered condition, These ancient wilderness

represent an important remnant of Canada's cultural heritage.

*Note by the author: The material for this article has been derived as part of a derailed on-going study covering Northwestern Quebec and Northeastern Ontario. Sources include archival map collections, survey records, and especially personal field inspections. Particularly useful were interviews with many of the elders of the Temeaugama Anishinabay on Bear Island and elders of adjacent Indian bands, some of whom are now deceased. This invaluable resource has provided deep insight largely unobtainable from the written record.

![]()

Click here to get to my canoe pages

Click here to get back to Erhard's Home Page